Experienced money launderers can increasingly exploit the often-fragmented nature of international anti-money laundering (AML) regulations.

Neutralizing these well-organized money launderers requires expertise with a broad range of tools and the ability to work seamlessly across jurisdictions.

Most financial institutions have the same issue — the AML department has more work than it does resources, namely money, time, engineers, and compliance expertise. AML departments have this problem partly due to the growth of their institutions. Therefore, by addressing these inefficiencies head-on, financial institutions would be able to optimize their processes, which in turn would enable an increased capacity to handle incremental volume without materially increasing expenses.

Let’s explore how best to conduct AML investigations:

Step 1: The Trigger Event

A Trigger Event in an AML investigation would simply mean the detection of suspicious activity. This trigger event is what brings the investigation before the eyes of an investigator, and it would contain information as to why the matter is considered suspicious or unusual.

Say, for instance, a financial institution (FI), that engages in the business of dealing with financial and monetary transactions such as deposits, loans, investments, etc. This trigger event is generally a transaction monitoring alert; in other circumstances, it may include an adverse media alert or a report from law enforcement. This report, generally known as a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR), is then submitted to the Financial Investigative Units (FIU), tasked with the main job of centralizing and gathering SARs related to criminal financial activity, including money laundering and terrorism.

It is crucial that investigators understand the trigger, but the trigger should not result in a myopic and subjectively biased approach to the investigation, which must be conducted objectively.

Step 2: Know Your Customer (KYC)

This is a very important step as it provides the foundational context against which the activity (or attempt) is assessed, evaluated, and understood. By completing this step, the investigator should have a good idea of the account activity expected to be seen in steps three through five.

KYC is necessary to ensure an investigator has covered all of the relevant bases.

Understanding the customer includes, but is not limited to:

- Who they are (i.e., their identity and cultural background, if applicable) and their risk status (e.g., politically exposed persons [PEPs])

- What they do (i.e., occupation, profession, or business) and the nature of risk associated with their occupation, profession, or business.

- How they earn their income and wealth.

- What products they hold, and why (e.g., the requirement for wires, remote deposit capture, etc.).

- Geographic footprint and operating environment (i.e., national/international risk ratings of countries the customer interacts with).

- Relevant adverse information associated with the customer or their business, close associates, or family.

- Non-adverse information that supports understanding of the customer.

Existing customer due diligence and enhanced due diligence information is obtained from institutional records and from hard copy records held locally at the branch level or by account and relationship managers.

The internet, open-source intelligence, and other database research can provide supporting information.

Step 3: Understand the Activity

In this step, a holistic and high-level view of the activity for the relevant review period is undertaken to determine whether the activity in the accounts (all of the accounts) appears to be in line with an investigator's knowledge of the customer (in step two), their business or occupation.

STEP 4: Eliminate the Norm

In alignment with the previous steps, the investigator doesn’t need to focus on activities that would be expected (or normal) by a customer. These norms are neither considered unusual nor suspicious.

In the context of a personal account, examples of normal activity might include grocery purchases, rent or mortgage payments, utilities, and personal spending consistent with the customer’s income, payroll, and wealth, as well as regular transactions processed through trusted payment processors for everyday expenses and remittances.

Business account examples of normal activity might include payroll, payments/receipts to or from legitimate suppliers commensurate with the business. Other overheads (e.g., rent, utilities, reasonable legal and accountancy expenses, IT and marketing, shipping costs, tax payments, fuel, etc.).

Step 5: Establish a Predicate Offense, Report, and Terminate Accounts

A useful place to start is to seek information about the commission of a predicate offense. For example, relevant adverse media might inform that the customer has been accused, charged, or convicted of fraud, drug trafficking, human trafficking, or tax evasion.

If a predicate offense can be established, any movement of the funds thereafter, with the intention to disguise or conceal those funds becomes suspicious activity, and therefore reportable.

If the predicate offense cannot be identified, then the remaining investigation will be focused on the money laundering aspect and may be reliant on using indicators (also known as red flags) in helping an investigator conclude (based on the low threshold of reasonable grounds to suspect) if money laundering (the commission or attempted commission of a money laundering offense) or terrorist financing is suspected.

This step also simply means submitting the Suspicious Activity Report (SAR), and to consider terminating the relationship if the risk of maintaining it is outside an organization’s risk appetite.

Conclusion

Institutions devote a massive amount of resources to financial-crime prevention and anti-money laundering efforts, mostly on procedure-driven activities, and better effectiveness.

While it’s possible to build and implement an AML investigative program from scratch, the amount of time and effort required to manually evaluate and report potentially fraudulent activities, especially as transaction volumes expand exponentially, can cause organizations to spend more time on investigative processes than line-of-business operations.

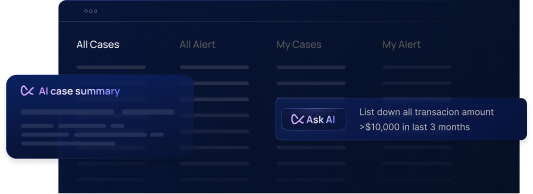

That’s where platforms like Flagright would be essential. It’s an AML compliance platform made for fintechs and neobanks that utilizes simple and standardized APIs, which makes integration much easier and 70% faster. No previous coding knowledge is required, which makes it easier to operate for compliance and operations teams. It’s a platform designed to detect and prevent malicious activity in real-time.

Ready to get the best of real-time AML compliance and fraud prevention for your business?

Contact Flagright to learn more.

.svg)