TL;DR

On July 8, 2025, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) fined Monzo Bank £21,091,300 for "inadequate anti-financial crime systems and controls" between October 2018 and August 2020. The fine—originally over £30 million but reduced 30% for early settlement—exposed how Monzo's explosive growth from 600,000 to 5.8 million customers far outpaced its compliance infrastructure. Key failures included allowing customers to open accounts with fake addresses like "Buckingham Palace," inadequate customer risk assessments, and most critically, opening over 34,000 high-risk customer accounts in direct violation of FCA orders between August 2020 and June 2022. This landmark case demonstrates that even celebrated UK fintechs face full banking standards for anti-money laundering (AML) compliance, with no "startup pass" for regulatory shortcuts.

Is Monzo Safe and FCA Regulated?

Yes, Monzo is safe and fully regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) as a licensed UK bank. Despite the £21.1 million fine, Monzo remains FCA-authorized and customer deposits are protected by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) up to £85,000 per person.

Monzo's Current Regulatory Status: Monzo holds a full UK banking license and operates under FCA supervision. The 2025 fine addressed historical compliance failures from 2018-2020, which the bank has since remediated. CEO TS Anil stated that Monzo's "learnings" led to "substantial improvements in our controls" and significant investment in financial crime prevention, with the FCA acknowledging the bank's remediation program.

What the Fine Means for Safety: The FCA penalty targeted operational compliance systems—not Monzo's financial stability or deposit security. The fine doesn't affect customer account safety, FSCS protection, or Monzo's ability to operate. First, during 2018–2020, the bank failed to design and maintain adequate onboarding, customer due diligence, and transaction monitoring systems commensurate with its risk.

Post-Fine Improvements: Following the FCA's August 2020 intervention, Monzo underwent a comprehensive independent review of its financial crime framework and implemented what the bank calls its "Financial Crime Change Programme." These upgrades include enhanced address verification, improved customer risk assessment tools, strengthened transaction monitoring systems, and increased compliance staffing. The FCA imposed strict requirements that Monzo had to meet before resuming normal high-risk customer onboarding.

Regulatory Oversight: As a fully regulated bank, Monzo operates under the same stringent standards as traditional high-street banks. This includes compliance with UK Money Laundering Regulations, Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements, and ongoing FCA supervision. The 2025 enforcement action demonstrates the regulator actively holds fintechs accountable to these standards.

Why Was Monzo Fined by the FCA in 2024/2025?

The FCA fined Monzo £21.1 million for failing to maintain adequate anti-money laundering systems between October 2018 and August 2020, combined with repeatedly violating regulatory orders by opening over 34,000 restricted high-risk accounts between August 2020 and June 2022.

The Timeline: The FCA investigation began after concerns emerged around 2020–2021 and came after a lengthy investigation first hinted at in Monzo’s 2021 annual report. On July 8, 2025, the FCA published its Final Notice detailing the enforcement action. The original penalty exceeded £30 million but was reduced to £21,091,300 because Monzo agreed to early settlement—a 30% discount standard in FCA enforcement.

The Core Issue: During Monzo's hyper-growth period—customer base surging from approximately 600,000 in 2018 to over 5.8 million by 2022—the bank's compliance infrastructure didn't scale proportionally. FCA Enforcement Director Therese Chambers stated that Monzo’s controls ‘fell far short of what we, and society, expect’ from a bank acting as a gatekeeper against financial crime, highlighting how regulators view fintech banks, brokerages and trusts as critical frontline defenses against financial crime.

What Made This Fine Particularly Severe: Most financial penalties involve technical compliance gaps. Monzo's case was more serious because the bank directly violated regulatory orders. After the FCA identified weaknesses in August 2020, it imposed a formal "Variation of Requirement" (VREQ)—essentially a regulatory ban prohibiting Monzo from opening accounts for high-risk customers until systems were fixed. Despite this explicit prohibition, Monzo opened accounts for over 34,000 high-risk customers over nearly two years, demonstrating what the FCA called "insufficiently robust governance" and accountability failures.

The Societal Impact: Banks serve as critical gatekeepers preventing criminal money from entering the financial system. When AML controls fail, institutions inadvertently facilitate money laundering, terrorist financing, fraud networks, and other financial crimes. The FCA emphasized that Monzo's shortcomings weren't isolated technical issues but "systemic failures" that could have been exploited by criminals.

What Were Monzo's Main Compliance Failures?

Monzo's compliance failures fell into four critical areas: address verification weaknesses, inadequate customer risk assessment, direct violation of FCA restrictions, and failure to scale ongoing due diligence systems.

1. Inadequate Address Verification

Monzo allowed customers to open accounts without proper address verification, accepting obviously false or implausible addresses. Between 2018-2020, Monzo didn't require proof of address for most new customers—a decision aimed at streamlining onboarding that backfired catastrophically.

The Problem: Monzo's systems only validated that an input resembled a UK postcode format. There was no independent check confirming the person actually lived at that address. Customers opened accounts using addresses like "10 Downing Street" (the Prime Minister's residence), "Buckingham Palace," and even Monzo's own headquarters. The bank's website actually advertised its easy sign-up with "no address verification" as a customer perk during this period.

Red Flags Missed: This lax approach created multiple warning signs: customers used P.O. boxes and mail-forwarding services (common in fraud schemes), entered foreign addresses formatted to look like UK postcodes, or gave identical addresses as other customers—suggesting potential money mule networks. Without address verification, Monzo couldn't even confirm all customers were UK-resident as legally required.

2. Inadequate High-Risk Customer Assessment

Monzo failed to implement an adequate customer risk assessment framework during onboarding, meaning it often couldn't identify when new customers should receive enhanced scrutiny.

Minimal Information Collection: Monzo collected only bare minimum information for identity verification, typically not asking about occupation, income sources, or intended account usage. This minimalist approach prevented reliable differentiation between normal customers and potentially high-risk individuals (those with links to high-risk jurisdictions, politically exposed persons, or suspicious attributes).

The 8.7% Problem: In 2018, Monzo tested a sample of approximately 69,000 existing customers against a fraud database and found 8.7% had red flags—a "high match rate" by industry standards. Many would have been classified as high-risk had proper screening occurred at onboarding. Because Monzo wasn't a CIFAS (Credit Industry Fraud Avoidance System) member until 2020, it missed early warning signs and onboarded customers with histories of financial crime.

3. Violating FCA Orders (Most Serious Failure)

Perhaps most egregiously, Monzo repeatedly violated direct regulatory orders. After identifying weaknesses, the FCA imposed a formal Variation of Requirement (VREQ) in August 2020, forbidding Monzo from opening accounts for high-risk customers until systems were fixed.

The Violation: Between August 2020 and June 2022, Monzo opened accounts for over 34,000 high-risk customers—exactly the type of customers the FCA had banned the bank from adding. This wasn't an accidental oversight but a systematic governance failure.

Chaotic Implementation: An independent review found Monzo's handling of the VREQ restriction was chaotic, with "insufficiently robust governance" and unclear accountability for enforcement. Some staff weren't even aware the restriction existed or didn't understand its importance. The bank implemented controls hastily without proper training or systems updates, so safeguards simply failed.

4. Failure to Scale Ongoing Due Diligence

Beyond onboarding, Monzo didn't adequately scale its ongoing customer due diligence and transaction monitoring as its customer base grew exponentially.

Stale Customer Information: Once accounts were opened, Monzo largely failed to revisit customer risk profiles or update information. The bank had no clear policy on when to refresh ID documents or request new information (proof of address, source of funds) even as years passed. A customer who opened an account with minimal checks in 2018 might still be transacting in 2020 with no further review, even if activity became atypical or risky.

Strained Transaction Monitoring: Monzo relied on rules-based transaction monitoring systems, but with limited customer data and risk segmentation, these likely produced ineffective alerts (either excessive false positives or missed suspicious patterns). Internal audits during 2019 flagged "particular concern" that the bank wasn't asking customers about intended account usage, making it "difficult to contextualize subsequent account activity" and spot money laundering red flags.

How Do Monzo's Failures Compare to Other UK Fintechs?

Monzo's £21.1 million fine is part of a broader pattern of compliance challenges across the UK fintech sector, with similar penalties hitting Starling Bank, Revolut scrutiny, and enforcement actions against other digital banks.

Starling Bank: £28.96 Million Fine (2024)

In 2024, the FCA fined Starling £28.96 million for AML control failures. The FCA found Starling's sanctions screening controls were "shockingly lax" and that Starling "repeatedly" violated an FCA requirement not to onboard high-risk customers—just like Monzo.

The Parallels: Starling grew from a startup to over 3.6 million customers in just a few years without scaling compliance appropriately. After an FCA review identified issues and imposed a high-risk onboarding ban, Starling went on to open approximately 49,000 high-risk accounts regardless—including hundreds of customers the bank had previously exited for financial crime concerns. The pattern mirrors Monzo's case almost exactly.

Revolut: AML System Scrutiny (2019)

Revolut faced intense FCA scrutiny in 2019 after media reports alleged it had temporarily disabled its automated AML transaction monitoring system due to excessive false positives. As one analyst noted in 2019 amid early warnings about Revolut, “Some of the cost reduction and speed may come at the expense of robust anti-money-laundering controls.” The idea that a regulated firm would switch off key anti-financial crime controls, even briefly, sent shockwaves through the industry and prompted FCA inquiry. In 2021, the FCA conducted a multi-firm review of financial crime controls , further intensifying regulatory scrutiny across the sector

Hyper-Growth Strain: At the time, Revolut was onboarding tens of thousands of customers rapidly, and the incident revealed how hyper-growth strains compliance systems. While Revolut's CEO denied wrongdoing, the episode demonstrated the structural tension between scaling quickly and maintaining robust controls.

Wise (Formerly TransferWise): $4.2 Million U.S. Fine (2023)

Wise, one of the UK's most prominent fintechs, was fined $4.2 million in 2023 by multiple U.S. state regulators for AML deficiencies. Regulators ordered Wise to strengthen suspicious activity reporting, customer due diligence, and independent oversight of its compliance program, including controls related to remittances. Around the same time, European regulators found Wise lacked proof of address for hundreds of thousands of customers, forcing large-scale remediation to collect missing KYC information.

International Scaling Issues: Wise's case demonstrated that fintechs expanding internationally at breakneck speed often discover compliance gaps only after regulators intervene.

The Common Thread

All these cases—Monzo, Starling, Revolut, Wise—share an imbalance between growth and control. Fintech firms typically start focusing on user acquisition, product innovation, and convenience, confronting the full complexity of regulatory compliance obligations only later. The FCA's enforcement actions play catch-up, emphasizing that being a newer fintech provides no excuse: firms holding millions of accounts face the same expectations as established banks.

Criminal Targeting: Challenger banks may even face higher scrutiny because criminals actively test them for weak points. The UK's 2020 National Risk Assessment flagged that "criminals may be attracted to the fast onboarding process that challenger banks advertise, particularly when setting up money mule networks."

What Does This Mean for UK Fintech Compliance?

The Monzo fine crystallizes critical lessons for the UK fintech sector: growth must be matched by compliance maturity, regulatory expectations apply equally to all banks regardless of age, and governance failures carry severe consequences.

FCA Expectations Are Non-Negotiable

The FCA operates under clear principles: AML systems must be "comprehensive and proportionate" to a firm's nature, scale, and complexity. A small fintech serving thousands might manage with lean compliance teams. But banks with millions of customers, like Monzo, must invest in robust systems—automated solutions, larger compliance staff, enhanced training.

Proportionality Requirement: The FCA explicitly noted that firms must keep customer risk assessment frameworks updated to reflect business model changes. Monzo's product offerings broadened and user numbers skyrocketed, but its risk assessment remained that of a much smaller startup—which the FCA deemed unacceptable.

Clear Governance and Accountability

One striking finding was unclear internal accountability for critical compliance tasks. The FCA expects fintechs to implement proper governance structures as they grow: boards or risk committees overseeing financial crime, regular board-level AML reporting, and designated individuals (like Money Laundering Reporting Officers) accountable under the Senior Managers & Certification Regime (SMCR).

Escalation Culture: The FCA expects a culture where compliance breaches are escalated and addressed, not lost in silos. When Monzo staff were unaware of critical restrictions, it revealed governance breakdown.

Rigorous Controls at Every Stage

The FCA expects digital banks to adhere to the same customer due diligence standards as traditional banks: verifying identity and address, understanding account purpose, applying Enhanced Due Diligence for high-risk customers, and maintaining ongoing monitoring with triggers for refreshing KYC information.

No Shortcut Through Monitoring: The FCA criticized some fintechs for relying on transaction monitoring to identify high-risk customers after the fact rather than vetting them properly upfront. The message: no matter how sophisticated your monitoring system, you must perform solid CDD at onboarding.

Industry-Wide Challenge

The UK's 2022 FCA challenger bank review found serious deficiencies across multiple firms: poor customer risk assessment frameworks (some had none at all), very limited KYC information collection during onboarding (not asking about income or occupation), and over-reliance on post-facto monitoring instead of upfront diligence.

The Tension: Fintech startups, armed with slick technology and investor pressure to scale, aim to be faster and cheaper than incumbents. But corners cut for speed have dire compliance repercussions. As one analyst noted: "Some of the cost reduction and speed may come at the expense of robust anti-money laundering controls."

How Can Fintechs Avoid Similar FCA Fines?

Fast-growing fintechs can avoid Monzo's fate by implementing scalable compliance from the start, adopting dynamic risk assessment, leveraging technology solutions, and prioritizing governance.

Implement Dynamic Risk Scoring from Day One

As customer numbers grow, move beyond one-time risk assessments to dynamic, data-driven risk scoring that continuously updates based on activities, behaviors, and new information. If a previously low-risk customer suddenly receives large international transfers, dynamic systems automatically elevate their risk rating and trigger review.

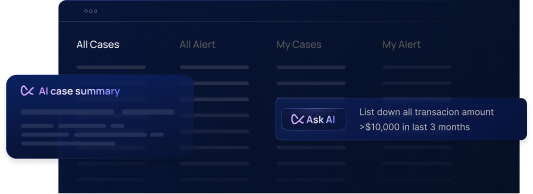

Why This Matters: Monzo's static approach (assuming most customers would use accounts uniformly) failed. Dynamic models challenge these assumptions by flagging outliers in real time. Fintechs can leverage machine learning and AI to detect unusual patterns across user bases—impractical with purely manual monitoring. This approach scales by design: as transaction volumes grow, algorithms sift through data to prioritize the riskiest cases for human review.

Embed Real-Time Onboarding Verification

Frictionless onboarding shouldn't mean lawless onboarding. Deploy tools to verify key customer information at account opening in real time: identity document verification with facial recognition, document verification APIs, and crucially, address verification using reliable databases.

Address Verification: Had Monzo cross-checked addresses against valid UK address databases, it would have immediately flagged "Buckingham Palace" or mismatched postcodes as exceptions requiring resolution before account opening. Today, electronic KYC services can confirm if an address exists and is linked to the applicant within seconds.

Real-Time Screening: New customers should be screened against sanctions lists, politically exposed persons (PEP) lists, and adverse media, with any hits reviewed before account activation. All checks can be automated to return results within seconds during signup flow.

Use Version-Controlled Rule Engines for Monitoring

As fintechs innovate with new products or face evolving criminal tactics, transaction monitoring rules must adapt continuously. Utilize version-controlled rule engines where every change to detection rules is tracked: who made the change, why, when, retaining previous versions.

Benefits: (1) Agility—Compliance teams can tweak and deploy new rules quickly in response to emerging risks rather than waiting for long IT development cycles. (2) Auditability—If regulators ask "why wasn't this flagged?", teams can show rule history and demonstrate when updates addressed gaps.

Practical Application: Monzo might have started with simple rules when small, but as it grew, it needed more complex scenarios. Version-controlled engines allow layering in new scenarios (flags for multiple accounts using the same address, rapid card re-shipments overseas) and refining thresholds as the customer base expands.

Maintain "Audit-Ready" Compliance Assurance

Fast-growth firms should adopt a mindset that regulators could review AML controls at any time, requiring demonstration of effectiveness. This involves:

Regular Management Information: Generate MI on compliance activities—number of suspicious transaction reports filed, high-risk customers onboarded, quality assurance check results. Have data on hand to show trends and justify resource decisions.

Proactive Internal Audits: Conduct independent reviews of financial crime controls periodically, even if not mandated. Monzo only underwent comprehensive review when the FCA forced it; other fintechs should proactively commission external expert reviews to identify gaps before regulators do.

Clear Audit Trails: Maintain documented justifications for key decisions. If a high-risk customer is allowed as an exception, document why and who approved it. If an alert closes as false positive, ensure analyst rationale is recorded.

Leverage Scalable Compliance Technology

Modern regtech platforms provide out-of-the-box tools far more scalable than building in-house systems from scratch. Platforms offering real-time transaction monitoring, dynamic risk scoring, and automated alert investigation can significantly enhance financial crime detection capabilities as firms grow (Case Study: B4B Payments)

Rapid Integration: Advanced compliance solutions can integrate in weeks rather than years, providing immediate capability boosts. These tools often include dashboards and reporting features making management oversight easier, aligning with FCA governance expectations.

Technology + People: Compliance technology must combine with trained professionals and sound policies. It's not a panacea but can dramatically shorten the time needed to reach robust compliance footing.

Foster Compliance Culture from Founding

Build cultures valuing compliance as integral to business, not as checkbox or obstacle. Leadership messaging matters: founders and executives should consistently emphasize that preventing financial crime is part of serving customers and society.

Practical Steps: As fintechs grow, invest in compliance talent—ensure Money Laundering Reporting Officers have sufficient seniority and voice, hire experienced compliance officers and financial crime analysts, and continually train all staff (including customer support and product teams) on AML red flags and responsibilities.

Scale Proportionally: If you double customers, anticipate compliance workload will also multiply (more onboarding reviews, more alerts, more reports) and budget headcount accordingly. The FCA will assess whether compliance functions are adequately resourced; being understaffed isn't a valid excuse for missing suspicious activities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Monzo still safe to use after the FCA fine?

Yes, Monzo remains safe for customers. The bank is fully FCA-regulated, deposits are protected by FSCS up to £85,000, and the fine addressed historical compliance issues from 2018-2020 that have since been remediated. The penalty targeted operational systems, not financial stability or account security.

What was the primary cause of Monzo's compliance failures?

The primary cause was explosive customer growth (from 600,000 to 5.8 million customers) far outpacing compliance infrastructure investment. Monzo prioritized rapid user acquisition over building proportionate AML systems, resulting in inadequate address verification, poor risk assessment, and insufficient transaction monitoring during critical growth years.

Did Monzo knowingly violate FCA orders?

The violation stemmed from governance failures rather than deliberate defiance. Monzo's internal organization of the FCA's high-risk customer ban was chaotic, with unclear accountability and some staff unaware the restriction existed. The bank implemented controls hastily without proper training or systems updates, causing systematic non-compliance rather than intentional violation.

How does Monzo compare to Starling and Revolut on compliance?

All three UK challenger banks faced compliance scrutiny during hyper-growth. Starling received an even larger £28.96M fine in 2024 for similar AML failures and violating FCA restrictions. Revolut faced investigation in 2019 for allegedly disabling AML monitoring systems. The pattern across all three demonstrates industry-wide challenges balancing rapid scaling with regulatory compliance.

Can the FCA shut down Monzo?

The FCA has authority to revoke banking licenses for serious, ongoing violations, but this is a last resort. Monzo's remediation efforts and cooperation (earning a 30% fine reduction) suggest the regulator views the issues as addressable rather than terminal. The bank continues operating under FCA supervision with strengthened controls.

What is a VREQ (Variation of Requirement)?

A VREQ is a formal regulatory tool where the FCA imposes specific restrictions or requirements on a firm's permissions. In Monzo's case, the August 2020 VREQ banned opening new high-risk customer accounts until compliance systems were fixed. Violating a VREQ is extremely serious, as it represents direct disobedience of regulatory orders.

How can customers tell if a fintech company has good compliance?

Check for: (1) Full FCA authorization (verify on FCA register), (2) FSCS deposit protection, (3) Clear privacy and security policies, (4) Transparent KYC processes requiring proper ID and address verification, (5) Active fraud protection and transaction monitoring, (6) Membership in fraud prevention systems like CIFAS, (7) No history of major regulatory fines (though past fines with demonstrated remediation may be acceptable).

What lessons should UK fintechs take from this case?

Key lessons include: scale compliance infrastructure in proportion to customer growth, never cut corners on address verification or customer risk assessment, implement robust governance with clear accountability for compliance functions, treat regulatory orders with absolute seriousness, invest in dynamic risk scoring and transaction monitoring technology, and foster compliance cultures where all employees understand their AML case management.

Key Compliance Recommendations for UK Fintechs

For Fast-Growing Digital Banks:

- Scale compliance teams and budgets proportionally with customer growth (if customers double, compliance resources must increase accordingly)

- Implement dynamic risk scoring that continuously updates customer risk levels based on activity patterns

- Deploy real-time address verification using authoritative databases at account opening

- Screen all new customers against sanctions, PEP, and fraud databases before activation

- Maintain version-controlled transaction monitoring rules that adapt to emerging threats

- Conduct quarterly internal compliance audits with external expert reviews annually

- Establish clear governance structures with board-level AML oversight and named accountable executives under SMCR

- Document all key compliance decisions with audit trails showing rationale and approvals

- Never implement regulatory restrictions hastily—ensure all staff understand requirements through comprehensive training

- Treat FCA Variations of Requirement (VREQs) with utmost seriousness, implementing immediate, well-governed compliance

For Compliance Officers:

- Build cases for compliance investment by showing risk exposure from inadequate controls (use Monzo as cautionary example)

- Implement "audit-ready" mindset: maintain MI dashboards showing compliance metrics regulators will request

- Test controls regularly through mystery shopping, data analytics, and simulated scenarios

- Establish whistleblower channels for staff to report potential compliance gaps confidentially

- Join industry fraud prevention networks (CIFAS, etc.) to access early warning systems

- Stay current with FCA guidance, enforcement actions, and Dear CEO letters addressing your sector

- Proactively disclose material compliance issues to FCA under Principle 11 before they're discovered through supervision

For Founders and Executives:

- View compliance as competitive advantage and customer protection, not merely regulatory burden

- Ensure compliance leaders have C-suite seniority and board access to raise concerns

- Budget compliance as percentage of revenue, increasing proportionally with scale

- Evaluate "build vs. buy" for compliance systems—specialized regtech often provides faster, better solutions than in-house development

- Never pressure compliance teams to approve borderline decisions for growth targets

- Communicate consistently that preventing financial crime is core to company mission

The Monzo case represents a watershed moment for UK fintech compliance. The £21.1 million fine sends an unambiguous message: explosive growth without proportionate compliance investment leads to severe regulatory consequences. Yet rather than viewing this as merely punitive, the industry should see it as a clarifying opportunity.

Fintech firms that proactively invest in scalable compliance infrastructure, leverage advanced technology solutions such as an AML compliance solution, establish robust governance, and foster cultures where preventing financial crime is everyone’s responsibility will not only avoid penalties but also build sustainable competitive advantages. Strong compliance enables secure growth, protects customers from exploitation by criminals, and builds the trust essential for long-term success.

The FCA's enforcement actions against Monzo, Starling, and others establish clear standards: innovation and agility cannot come at the cost of integrity. Digital banks holding millions of accounts shoulder the same gatekeeping responsibilities as century-old institutions. Fintechs that embrace this reality—building compliance excellence into their DNA from day one—will thrive. Those that don't risk becoming the next cautionary tale in the regulator's enforcement notices.

.svg)

.webp)

.webp)