Introduction: The Rise of APP Scams in the Instant Payments Era

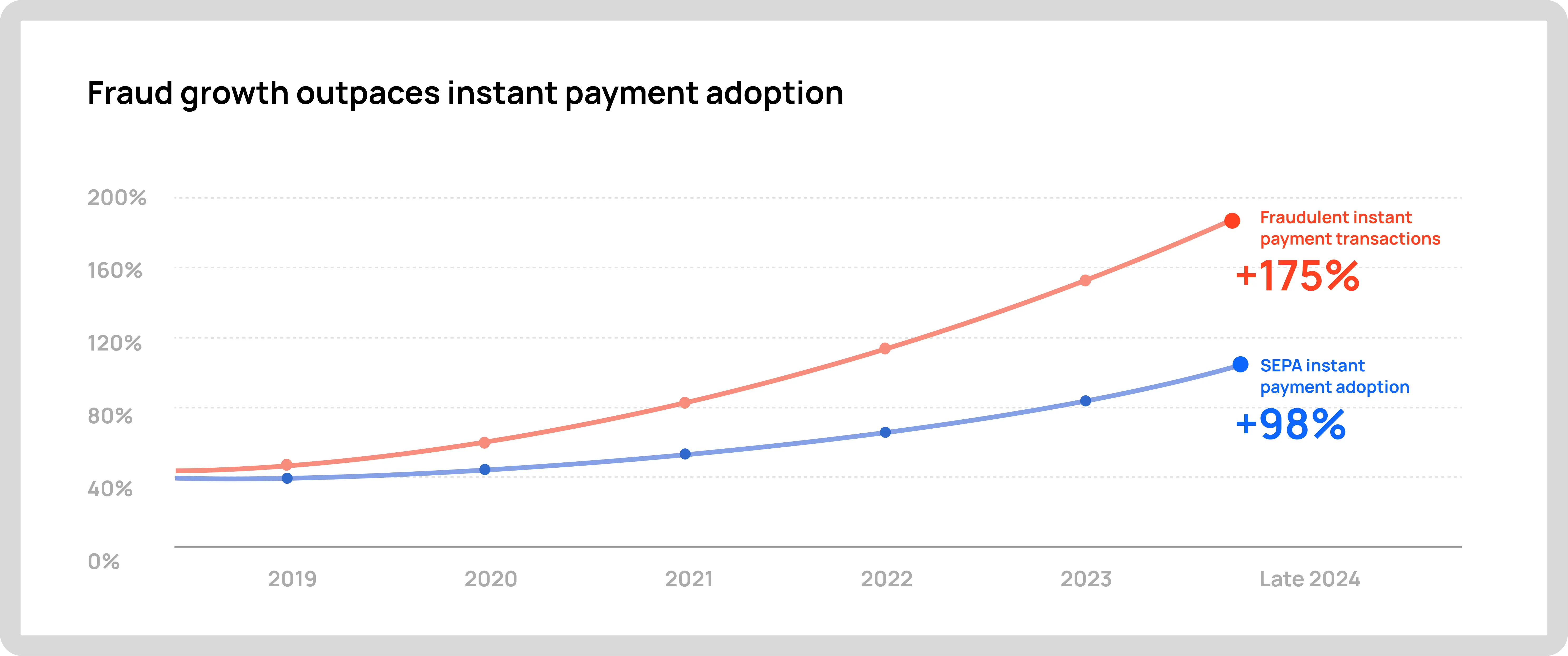

Authorized Push Payment (APP) scams, where victims are tricked into sending money to fraudsters, have surged alongside the rapid rollout of SEPA Instant payments across Europe. Instant credit transfers are becoming mainstream; by late 2024 about 16% of all SEPA credit transfers were real-time, up from under 10% just a few years prior. Unfortunately, fraud has escalated even faster. The number of fraudulent instant payment transactions jumped 175% in recent years, far outpacing the ~98% growth in overall instant payment volume. In 2024 alone, total payment fraud in the EEA reached €4.2 billion (up 17% year-on-year), with credit transfer fraud (including instant payments) rising 24%. Regulators note that APP scams are the chief driver of these losses, often causing “high damages per fraudulent transaction”. For example, the average fraudulent SEPA Instant transfer is around €1.4k, which, while lower than the ~€3.6k average for traditional wire transfer fraud, underscores that each successful scam can extract significant funds. In aggregate, this is inflicting huge harm on consumers, 85% of credit transfer fraud losses in 2024 were borne by customers (since the payments were authorized by victims). The stage is set for a pressing question: Do our current suspicious activity reporting (SAR) thresholds and triggers adequately capture this new wave of low-value, high-frequency scam activity?

Real-Time Payments vs. Traditional AML Detection

The ultra-fast, fragmented nature of instant payments is straining traditional AML controls. In the past, banks could rely on nightly batch processes or manual reviews to flag unusual transactions before money moved. Now, funds can disappear across multiple banks and even countries within minutes, effectively laundered before the victim or bank even realizes. Fraudsters exploit the narrow intervention window of SEPA Instant, transfers settle in 10 seconds or less, 24/7/365, leaving virtually no downtime for compliance teams to “catch up” on alerts. If an account is compromised or being used as a mule, stolen funds may be rapidly layered through dozens of small, instant transfers to other accounts (or into crypto exchanges), often crossing borders to evade recall. This speed and fragmentation undermine the effectiveness of traditional AML detection in two key ways:

- Delayed Suspicion Formation: Banks often identify suspicious activity by observing patterns over time, e.g. a series of large transactions or repeated structuring below a threshold. But with instant payments, the entire pattern (multiple incoming credits to a mule, then an outbound sprint) might execute in an hour. By the time a bank’s monitoring system or analyst deems the activity suspicious enough to file a SAR, the money is long gone. The SAR becomes merely after-the-fact paperwork, with little chance to freeze funds or assist recovery.

- Fragmented Visibility: In APP scam schemes, no single institution sees the full trail. The victim’s bank sees one outgoing transfer; the receiving bank sees one incoming credit (perhaps unremarkable on its own). The funds may hop through multiple PSPs and jurisdictions, such that each sees only a slice. A mule account might receive many small payments from different victims across Europe, “dozens of incoming instant transfers from across Europe”, a classic mule pattern. But those victims’ banks are scattered; only the mule’s bank sees the convergence, and if that bank’s monitoring isn’t real-time or tuned to mule typologies, the red flag may be missed. Essentially, the fast, cross-border nature of instant payments can outpace both detection and coordinated SAR filing.

Adding to the challenge, compliance teams are under pressure not to delay customer payments. Holding up an instant transfer for investigation undermines the promise of real-time service. Yet letting it flow through unchecked risks enabling fraud. It’s a perilous trade-off: either delay the payment (violating the “instant” promise) or process it and potentially facilitate crime. Regulators have made clear that speed is no excuse for letting suspicious transfers slip by, all normal AML and sanctions obligations still apply at full throttle. The result is that many institutions find their legacy monitoring systems (built for batch processing and T+1 review) are ill-suited to the instant era. This gap directly impacts SARs: if you can’t detect the suspicious pattern in real time or near-real-time, your SAR filing will inevitably be delayed, diminishing its usefulness. In sum, instant payments demand instant vigilance, something traditional SAR regimes struggle to achieve.

Do Current SAR Thresholds Fit Modern Scam Patterns?

Suspicious Activity Reports in many jurisdictions have historically been associated with thresholds or obvious red flags, e.g. unusual cash deposits over €10k, transfers to high-risk countries, etc. Many banks’ internal SAR triggers still skew toward value-based criteria: a transaction or series of transactions exceeding a certain amount, or a sudden balance spike, prompts review. Behavior-based alerts (patterns of activity inconsistent with a customer’s profile or known typologies) also exist, but these too have often been calibrated with traditional money laundering scenarios in mind (e.g. structuring just under reporting thresholds, large international wires to secrecy havens).

Modern APP fraud flows turn these assumptions on their head. Instead of a few large transfers, scammers often use many small ones. They deliberately stay under amounts that might individually stand out. For example, rather than moving €50k in one go (likely to trigger an alert), a mule account may receive ten payments of €5k from different senders and quickly forward them onward. Each component looks “normal” in isolation, €5k isn’t necessarily suspicious for a checking account, but the collective pattern is illicit. If a bank’s SAR program only flags single transactions above a fixed value, it will miss this activity. Even aggregating over a day, some mule accounts might keep each transfer small enough or spaced out enough to avoid simple thresholds.

Moreover, APP scam transactions often closely mimic legitimate payments (they are authorized by the customer and may reference real-looking purposes). This makes rule-based detection harder. The suspicious typology lies in the context and behavior: e.g. an elderly customer suddenly sending five transfers in an hour to new payees, or an unemployed student’s account receiving multiple incoming credits from unrelated people abroad. These are exactly the kinds of patterns that don’t fit the old SAR triggers well. Traditional AML systems might ignore the first few small transfers or chalk them up to normal P2P activity, thus delaying suspicion until much later.

Regulators are increasingly asking whether the current regime is adequate. The data on APP fraud has been a wake-up call: billions disappearing via authorized scams with little recourse has prompted soul-searching on whether banks’ AML controls should do more earlier. For instance, should a series of outgoing payments by an elderly user to a new beneficiary trigger not just a fraud alert, but an AML suspicious activity report? And should banks be empowered (or expected) to delay or block transactions that fit an APP scam pattern under their anti-financial crime mandate? These questions are mounting, because in many cases the answer has been “No” under legacy approaches, once a customer authenticated a payment, banks felt obliged to execute it and perhaps only later file a SAR if things didn’t add up.

Clearly, modern scam typologies are exposing gaps in the SAR regime. Value thresholds alone are a blunt instrument; fraudsters circumvent them by fragmentation. And many monitoring rules haven’t kept pace with scammer tactics like mule account networks. The result is that suspicious patterns go unreported to FIUs (Financial Intelligence Units) until they become quite blatant or high-value, by which time the trail is cold. In the APP fraud era, that “other data” (the cross-account, cross-bank picture) might only come to light if we adopt a more aggressive, pattern-based approach to SARs.

EU Policy Shifts: Toward Behavior-Based, Lower-Threshold Reporting

European AML frameworks are responding to these new threats by pushing for a more typology-driven and proactive SAR culture. Under the upcoming 6th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD6) and the parallel AML Regulation, financial institutions are explicitly expected to strengthen their detection frameworks and report suspicious activities promptly to FIUs. This means moving away from a “tick-box” approach and towards truly risk-based monitoring that can capture emerging fraud patterns. Notably, AMLD6 even mandates integrating technological tools to enhance AML effectiveness, a clear signal that advanced analytics (like AI-driven pattern recognition) should be deployed to spot suspicious behaviors that simpler rules might miss.

Crucially, 2024/2025 sees the launch of a new EU Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA). From 2025 onward, AMLA will have direct supervision over certain “high-risk” institutions and the power to intervene swiftly if it detects serious AML control failures. This centralized authority is expected to harmonize expectations across member states, and one likely emphasis is on improving suspicious activity reporting for new threat areas like fraud-enabled money laundering. The European Banking Authority (EBA) has already signaled its stance: fraud risks are significantly higher (up to 10× higher) in instant payments than in traditional transfers, so banks must implement robust real-time fraud detection and suspicious activity controls. In other words, regulators want SARs to be driven less by static thresholds and more by dynamic risk indicators, the pattern of transactions, the profile of those involved, and known typologies of criminal behavior.

This shift is evident in how supervisors talk about scams. They emphasize that fraud and money laundering now converge in channels like instant payments, and that banks must treat scam proceeds with the same urgency as classic AML cases. For example, money mule accounts that receive scam funds are essentially nodes in a laundering scheme. Regulators expect banks to detect and report those as suspicious transactions, not shrug them off as “just fraud issues.” Indeed, supervisors will hold institutions accountable for detecting and reporting scam-related flows as part of their AML/CFT duties. This is a marked cultural change: historically, a fraud case might be handled by a separate fraud team, and only if it rose to a certain severity would an AML report be considered. Now, the directive is to blur those distinctions; if it quacks like money laundering (even if it originated as an online scam), file a SAR.

Additionally, upcoming payments regulations (PSD3 and the new Payment Services Regulation) complement the AML framework by implicitly lowering the bar for intervention. PSD3 is set to strengthen fraud prevention requirements and liability: banks and PSPs will be obligated to implement measures like Confirmation of Payee name-checks to curb APP fraud, and importantly, PSPs will have an explicit right to block or delay a payment when their systems detect strong evidence of fraud in progress. This is a significant change from today’s environment, effectively encouraging firms to act on suspicion immediately (even if it means pausing an instant transfer) rather than feeling forced to execute every customer-authorized payment. In practice, that means if your real-time monitoring flags a likely scam, you not only can stop it in flight, you’re expected to. And where there’s strong suspicion of criminal proceeds (even low-value), a SAR should follow as a matter of course.

Put simply, EU regulators are recalibrating the system toward “when in doubt, report”. Financial institutions are not expected to prove a crime before filing; they are not expected to confirm crimes, only to recognize activity that looks unusual or suspicious. Especially under AMLA’s eye, the institutions that err on the side of filing (even for lower-value or hard-to-classify suspicious patterns) will be seen as aligning with the new norms. Those clinging to high internal thresholds (“we only file if it’s above €X or clearly criminal”) may find themselves criticized for missing the early warning signs.

Supervisory Expectations and PSD3: Lowering the Bar for SARs

Regulators across the EU have been communicating some common expectations that directly affect SAR policies:

- Suspicion Triggers, Not Confirmation: Compliance officers often wrestle with uncertainty, Is this just unusual or truly illicit? Historically, some banks hesitated to file SARs unless they felt sure of a likely offense (to avoid false alarms). But guidance now emphasizes that if you have a reasonable suspicion, even if the exact crime or scam isn’t fully clear, you should file. This means SAR thresholds in practice should be low: the moment a pattern of transactions raises a red flag (even a small one), that should be enough to warrant a report. Waiting for more evidence or higher amounts is discouraged.

- “Smaller” Transactions Count: Many APP frauds involve amounts well below the traditional high-risk thresholds. Regulatory rhetoric indicates that no amount is too small if it’s linked to criminal activity. For example, the US SAR rules (while not directly applicable to the EU) explicitly note that even transactions under $5k can trigger SARs if they appear structured or serve no lawful purpose, acknowledging that relatively small sums can point to larger schemes. European FIUs similarly do not impose a monetary floor for reporting, a cluster of €500 transfers can be just as suspicious as a single €50k wire. The “reporting bar” is effectively being lowered by urging firms to focus on behavior and context, not just dollar (or euro) value.

- PSD3 and Consumer Protection: The upcoming PSD3/PSR framework explicitly tackles APP scams by shifting more responsibility onto banks/PSPs for preventing and responding to fraud. One proposal will make providers liable for certain impersonation scam losses and require refunds to victims in many cases. This creates a powerful incentive: if banks are on the hook to reimburse scam victims, they will need to identify scam-related transactions early and often. Filing SARs on mule accounts and suspicious recipients (even for low amounts) becomes not just an AML duty but a part of institutions’ risk mitigation to avoid liability. Regulators implicitly expect that with greater liability comes more vigilance, firms that proactively report and address scam networks will fare better under the new regime.

- Faster Reporting Cycles: There’s also movement towards speedier SAR filings. While the legal deadline to file a SAR (once suspicion is formed) might remain (e.g. 30 days in many jurisdictions), supervisors want to see “ongoing monitoring” catch issues sooner. The emphasis on continuous, real-time monitoring in AMLD6 and the Instant Payments Regulation means banks should be detecting suspicious patterns as they happen. If a mule account starts behaving badly on Monday, waiting until the end of the month to file a SAR is far from ideal. We can expect regulators (and AMLA) to scrutinize how quickly institutions escalate suspicions internally and to the FIU. The trend is toward “earlier SARs on emerging patterns” instead of late-stage reporting on well-established cases.

In summary, the direction from both policy (AMLD6, PSD3) and supervision is clear: lower your thresholds, broaden your definition of suspicious behavior, and report promptly. A more behavior-led, typology-driven SAR culture is being actively cultivated to combat instant payment fraud. Banks and fintechs should align their internal policies now, it’s better to “over-report” bona fide suspicious patterns than to be the institution that missed the memo on the scam epidemic.

Practical Steps for PSPs and Fintechs: Adapting to the New Normal

Facing these shifts, heads of compliance, MLROs, and monitoring teams at banks and PSPs need to adjust their approaches. Below are practical strategies to ensure your institution catches more scam-related activity and meets the new expectations:

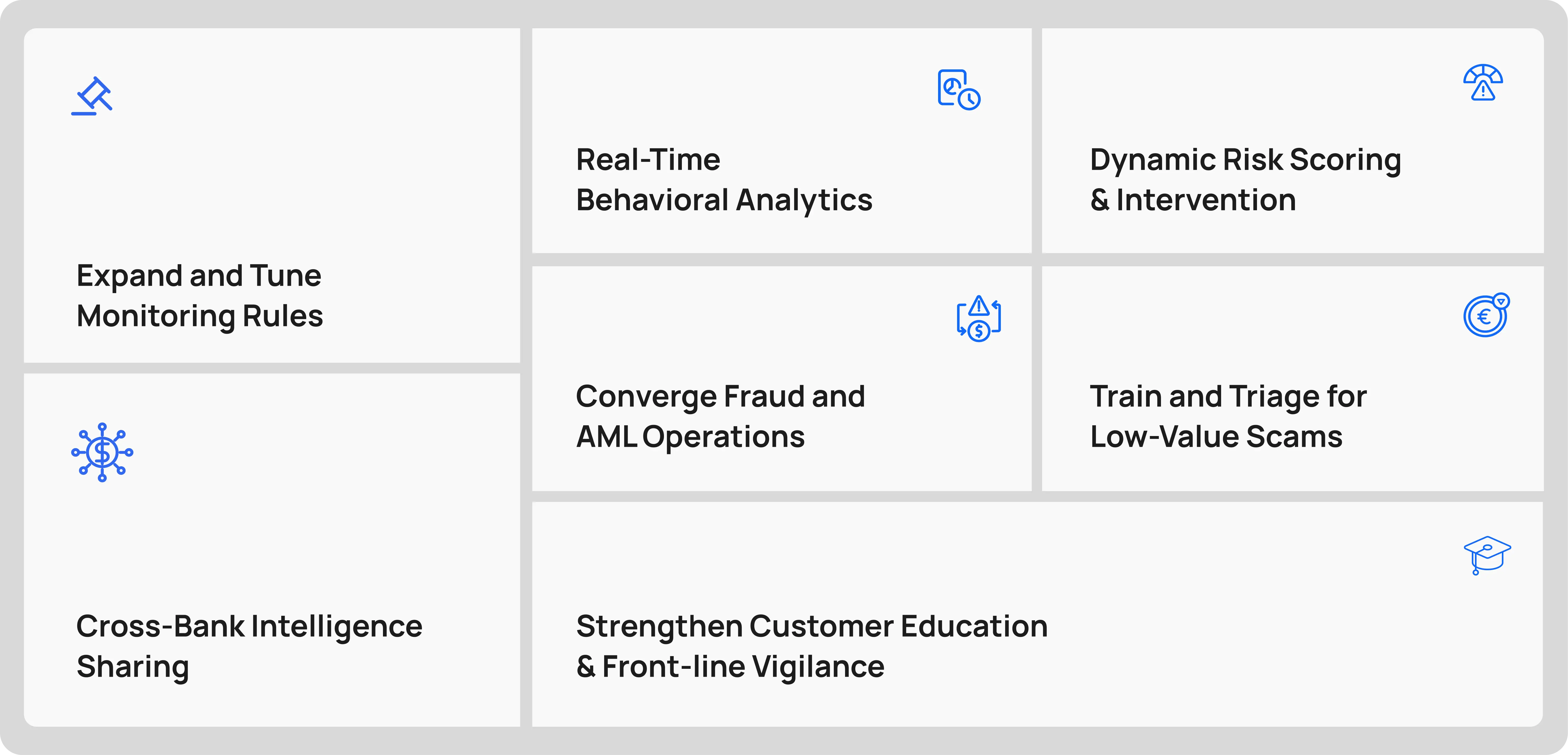

- Expand and Tune Monitoring Rules: Update your transaction monitoring scenarios to capture the hallmarks of APP fraud and mule accounts. For example, set rules to flag when an account that’s usually quiet suddenly receives multiple incoming credits from different payers and rapidly forwards funds. Or when a customer sends an unusually high number of new payees money in a short span. Lower the value thresholds in these rules; don’t ignore a string of €300 transfers if they fit a scam typology. The goal is to identify patterns (speed, volume, origin/destination) rather than rely on any single large transaction. Transaction monitoring should incorporate known fraud patterns, e.g., a rapid sequence of inbound credits followed by an outbound to crypto (a common mule behavior). If your current rules would overlook that because each credit is small, it’s time to recalibrate them.

- Real-Time Behavioral Analytics: Embrace solutions that analyze customer behavior in real time, not just in batches. Establish a baseline for each customer’s typical transaction behavior and have your system alert on deviations instantly. For instance, if a normally low-activity account tries to initiate a high-value or cross-border instant transfer, that anomaly should trigger an immediate review or a step-up verification before the funds leave. The aim is to detect and interdict potential fraud during the payment flow, not hours later. Modern cloud-based fraud engines using machine learning can be a big help here, they can crunch streaming data to spot signs of account takeover, mule activity, or social engineering as they unfold, even when the pattern is subtle.

- Dynamic Risk Scoring & Intervention: Implement dynamic, real-time risk scoring for transactions and customers. Factors might include device fingerprint, geolocation, unusual time of activity (e.g. wee hours transactions), recent scam reports linked to a payee’s IBAN or phone number, etc. When a transfer’s risk score crosses a certain threshold, be ready to take action in the moment: require Strong Customer Authentication (if it was originally exempt), ask the customer for additional confirmation of the payment purpose, or even delay/block the transaction for manual review if the risk is acute. Notably, the forthcoming PSD3 rules explicitly empower providers to pause payments when fraud is suspected. Use that power. It’s far better to inconvenience a customer briefly than to let them be scammed out of their savings. Ensure your policies detail when and how operations can intervene, e.g. a rule that if an elderly account holder is sending >€1k to a first-time payee flagged as high-risk, the payment is held pending a call to the customer. Such proactive measures can stop scams in real-time and generate useful intelligence (if the customer confirms it was a scam attempt, you have clear grounds for a SAR).

- Cross-Bank Intelligence Sharing: Fraudsters often hop between institutions, the account that receives stolen funds might be at a different bank than the one where the victim holds an account. To counter this, participate in industry information-sharing. The new EU framework under PSD3 will facilitate sharing fraud data (e.g. known mule IBANs, scammer identities) between PSPs. Within GDPR limits, make use of such channels. If you learn that a certain account or card number is implicated in scams at other banks, feed that into your monitoring systems (e.g. auto-block payments to that IBAN or do enhanced due diligence on that customer). Consortium data and shared blacklists can greatly enhance your detection models. In practical terms: join fraud intelligence forums, use third-party databases of mule accounts, and ensure your fraud and AML teams consume these external risk alerts regularly. Many scam networks can only be unraveled by connecting dots across institutions, don’t operate in isolation.

- Converge Fraud and AML Operations: Tear down the wall between your fraud detection team and your AML compliance team. In the instant payments world, fraud prevention and AML are two sides of the same coin. Consider using unified platforms or workflows that allow analysts to see both fraud indicators and AML risk flags together. If a series of small incoming transfers wouldn’t normally trigger an AML alert by themselves, a well-integrated system might still flag the account because those senders were recently victims of fraud (a context a pure AML system might miss). By evaluating transactions for fraud and AML suspicions in parallel, you get a more complete picture and can escalate cases more effectively. For example, a real-time platform could simultaneously block a suspicious instant transfer and create a case in the SAR reporting queue with all relevant info attached within seconds. This kind of joined-up approach means nothing falls through the cracks simply because it was classified as a “fraud issue” versus an “AML issue” it’s all financial crime.

- Train and Triage for Low-Value Scams: Revise your investigative workflows to ensure lower-value alerts get attention when they fit a scam pattern. It’s common for compliance teams to prioritize alerts by dollar amount, a €100k wire might get immediate review while a €500 odd transfer is deferred. Adjust this practice: if an alert is generated because the pattern matches known mule behavior, treat it with urgency regardless of the Euros involved. Develop triage criteria that elevate cases like “multiple customers reporting authorized payment fraud involving the same beneficiary” or “account receiving lots of small credits then going empty”. These scenarios should prompt swift investigation and, where warranted, a SAR filing, even if the sum of money isn’t huge. Your analysts should be trained that “suspicious is suspicious” even at €50, especially if it appears to be part of a broader fraud chain. Many institutions also find it helpful to do thematic reviews: e.g., periodically analyze all transfers to certain high-risk fintechs or crypto exchanges under a small amount (say <€1000) to spot any patterns that were missed in real time. This can uncover mule accounts or scam funnels that individual alerts didn’t reveal.

- Strengthen Customer Education & Front-line Vigilance: While not directly an SAR process, educated customers can reduce the incidence of scams (meaning fewer dirty transactions to launder). Many banks now display fraud warnings in-app if a transfer looks suspect (“This IBAN has been reported in scam cases, are you sure?”). Make use of such friction. Encourage customers to pause and verify before sending money, especially if the request came via unsolicited communication. Internally, empower your front-line staff (branch tellers, call center) to spot red flags like a nervous customer making an unusual transfer, they might be on the phone with a scammer. Early intervention can stop fraud before funds enter the mule network, saving everyone downstream effort. And if an incident is narrowly averted, you still gain intelligence (e.g. details of the social engineering attempt) that can feed into typology updates and perhaps prompt a defensive SAR (reporting an attempted fraud scheme/mule account).

By implementing these measures, PSPs and fintechs can better detect, disrupt, and report scam-related money laundering. The overarching theme is to move faster and be more curious about small anomalies. Use real-time data, collaborate across departments and institutions, and don’t hesitate to escalate a case just because it’s “only a few hundred euros”, those euros might be the tip of a much larger fraud iceberg.

Real-Time Tech and Explainable AI: Staying Ahead of Scams

One silver lining is that technology is rising to meet the challenge. A new generation of real-time AML platforms and explainable AI (XAI) tools can help institutions spot fraud-driven laundering sooner and with greater clarity. These systems are designed from the ground up for speed, integration, and intelligence:

- Unified Real-Time Compliance Platforms: Instead of patching together separate fraud detection, AML monitoring, and case management tools, firms are adopting unified solutions. For example, Flagright’s platform integrates AML transaction monitoring, watchlist screening, fraud detection, and case management in a single system. This eliminates the silos and ensures that when a suspicious instant payment hits, the platform can cross-reference multiple risk signals at once; fraud patterns, watchlists, customer profiles, and raise one coherent alert for analysts. Importantly, such platforms operate 24/7 with sub-second decision speeds: Flagright’s engine can evaluate transactions and apply complex rules within fractions of a second. That means even in a 10-second SEPA Instant window, the system can auto-clear low-risk payments and flag high-risk ones in time to stop them. The result is a much higher chance to intervene on scams and to generate timely SARs with comprehensive supporting data (since the case data is automatically compiled across all risk dimensions).

- Advanced Analytics and AI (with Transparency): Modern AML solutions incorporate machine learning models that can identify anomalous patterns or combinations of risk factors that human-defined rules might overlook. For instance, an AI model might learn the subtle behavior signature of an investment scam mule (maybe a certain pattern of small deposits from retail investors followed by a lump-sum outgoing to a shell company) that isn’t explicitly coded in rules. Explainable AI is crucial here, banks and regulators rightly demand to know why an AI flagged something. The latest systems therefore provide human-readable explanations for each alert. If an AI-driven monitor flags a transaction or account, the platform will articulate the key factors: e.g. “This transfer to account X is unusual because the account receiving funds has a pattern of rapid withdrawals and links to previously reported mule accounts.” Such transparency helps compliance teams trust AI alerts and act on them. It’s no use getting a black-box score that says “97% suspicious” with no context, that might sit ignored. With explainable AI, every alert comes with the rationale (transaction patterns, customer’s historical profile, peer group comparisons, etc.), so investigators can quickly grasp why it’s suspicious. This not only speeds up the decision to file a SAR, but also means the SAR report itself can be richer (containing the AI-identified patterns as part of the suspicion narrative).

- Reducing False Positives, Focusing on True Risk: A well-tuned combination of rules + AI can dramatically cut down false positives (noise) and highlight true positives (meaningful alerts). Given that traditional transaction monitoring often overloads teams with low-value alerts, adding AI that learns from feedback, which alerts truly indicated fraud vs. which were innocent, can refine the system over time. For example, Flagright’s platform uses machine learning to recognize false matches or benign patterns faster than static rules. Fewer false alerts mean compliance analysts can devote time to the alerts that matter, including those previously “invisible” small scam patterns. As regulators increasingly expect firms to handle high alert volumes with efficiency, AI provides a way to scale: it’s like having an extra pair of (very fast) eyes on all transactions at once. Crucially, because these AI systems are explainable and auditable, a bank can demonstrate to examiners how its AI is making decisions and be confident that nothing critical is being blindly automated without oversight. In essence, real-time, explainable AI-driven monitoring gives institutions an edge in catching fraud-driven money laundering early, without drowning in false alarms.

By investing in such real-time risk infrastructure, financial institutions not only protect themselves and their customers better, they also position themselves as proactive partners to regulators. A bank that can show it uses an advanced platform to stop instant payment scams in-flight and promptly report them (with clear evidence) will stand in good stead with the AML supervisors, and it will avoid the reputational and financial damage that comes from being embroiled in a large-scale scam scandal.

Conclusion: 2026 and Beyond, Don’t Get Left Behind

As we head into 2026, all signals point to an environment where regulators expect the industry to treat scam-related flows as inherently suspicious and SAR-worthy, even at low amounts. The era of “wait until it’s obviously big or bad enough” is over. We may soon see examiners criticizing firms that fail to file SARs on patterns that, in hindsight, indicated APP scam networks (even if individual transactions were small). Financial crime compliance is shifting from a reactive stance to a proactive, preventive one. Firms that embrace this, by lowering their internal thresholds, leveraging typology-driven monitoring, and filing SARs at the first whiff of laundering via fraud, will not only meet their legal obligations but also help choke off scam networks earlier in their lifecycle.

Moreover, the broader regulatory and liability landscape is raising the stakes. With PSD3/PSR likely making banks more financially accountable for fraud losses, and AMLA ready to wield enforcement power for AML lapses, there is tangible risk in being a laggard. As one analysis noted, forward-looking institutions are already investing in stronger fraud defenses and integrated AML controls now, rather than waiting to be forced by regulation or suffer losses. Those who delay action, sticking to old thresholds or slow processes, may find themselves facing not just increased fraud costs but also regulatory penalties and public criticism for failing to protect customers. On the flip side, those who innovate in this space can turn it into a competitive advantage: being known as a bank that keeps customers safe (catching scams early, reimbursing when needed, and aiding law enforcement with quality SARs) builds trust and satisfies regulators.

In summary, instant payments are here to stay, and so are the fraud risks that come with them. The compliance leaders in 2026 will be the ones who adapt their SAR regimes to this new reality, treating speed as essential, treating small anomalies as meaningful, and treating fraud and AML as a unified mission. By doing so, they won’t just avoid being “left behind”; they’ll be at the forefront of the fight against financial crime, helping to ensure that the fast payments revolution doesn’t become a bonanza for scammers. The message from regulators is clear: don’t wait for a €1 million transaction to worry about money laundering; the €1,000 transfer you stop today could be the clue that prevents a €1 million fraud tomorrow. Adjust your triggers accordingly, invest in the right tools, and foster a culture that always stays one step ahead of the scammers. That is the path to success, and compliance, in the instant payment age.

.svg)

.webp)