APP Scams Are Europe’s Dominant Payment Fraud Threat

Authorized Push Payment (APP) scams; where victims are tricked into pushing their own money to fraudsters, have surged across Europe. In the latest data, these scams are rising rapidly in both frequency and value, overtaking traditional card fraud by sheer losses. In 2024, the average fraudulent credit transfer (often an APP scam) exceeded €2,000, far higher than the average card fraud transaction, making each scam incident costly. Critically, manipulation of the payer (the European Banking Authority’s term for APP scams) is now the top fraud type for credit transfers, accounting for over half of all fraud losses in that payment channel. In practical terms, this means impersonation and social engineering scams have become the primary way criminals defraud consumers, eclipsing unauthorized card or account takeovers.

These APP scams have proliferated especially via instant and online bank transfers. Real-time payment networks give fraudsters immediate access to moved funds, helping credit transfer fraud losses reach €2.5 billion in 2024, about 60% of all EEA payment fraud by value. Indeed, credit transfers have now overtaken cards as the largest fraud category by value, chiefly due to the explosion of APP scams riding on faster payment rails. In short, Europe’s fraud battlefield has shifted: the biggest losses now stem from victims being tricked into authorizing payments to criminals, rather than from unauthorized transactions caught by traditional controls.

From Fraud Issue to AML Priority: Why APP Scams Are Now a Compliance Concern

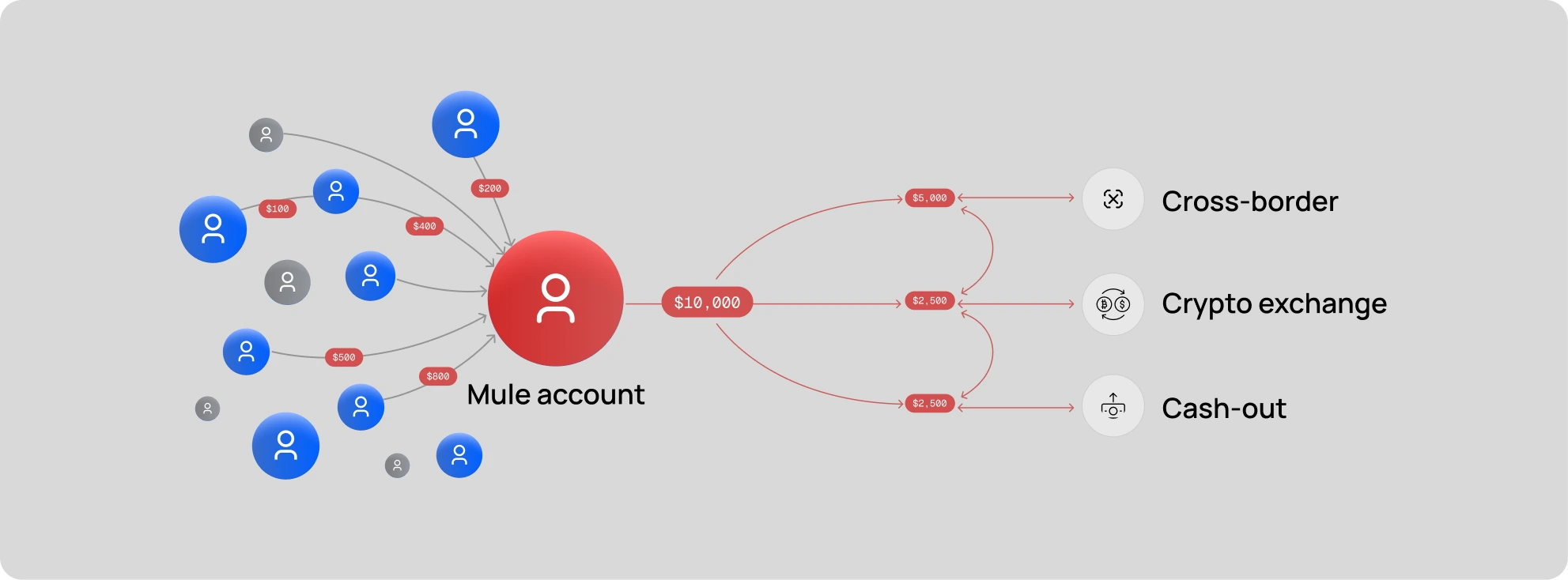

Historically, APP scams were managed as a “fraud” problem, a consumer protection issue handled by fraud departments. But today, regulators increasingly view them as a money laundering and AML concern as well. The logic: when a victim is conned into sending money to a scammer’s account, those funds often vanish across borders within minutes, effectively laundered through mule accounts before the victim even realizes the fraud. The 2025 EBA/ECB report underscores this cross-border laundering element: a large share of fraudulent credit transfer funds quickly move overseas or into obscure accounts, mirroring classic money laundering tactics of layering funds through foreign banks. In many cases, the very same accounts used to receive scam proceeds turn out to be part of broader mule networks that shuffle illicit money through multiple hops. E-money wallets, fintech bank accounts, and crypto exchanges frequently feature in these schemes, their rapid onboarding and transfer capabilities can attract fraud proceeds that are swiftly cashed out or converted.

In effect, APP fraud blurs the line between fraud and money laundering. The crime generating the funds (fraud) and the process of moving those funds (laundering) occur almost simultaneously. For example, if one account suddenly receives dozens of incoming instant transfers from individuals across Europe, a hallmark of a mule account collecting scam payments, it’s both a fraud incident and an AML red flag. In the past, such activity might only trigger a fraud investigation (to identify and block the mule). Now, regulators expect it to trigger suspicious activity monitoring and reporting as well.

A driving factor for this shift is the stark reality of who bears the loss. In 2024, victims (payment service users) absorbed 85% of all credit transfer fraud losses. Unlike unauthorized card fraud, where banks often reimburse customers, APP scam victims usually have no automatic reimbursement right under current laws, since they approved the payment. With billions disappearing via authorized scams and victims left holding the bag, authorities are asking hard questions: Are banks doing enough to intercept scam-related flows before the money disappears? Should a pattern of large outgoing transfers fitting an APP scam profile trigger not just a fraud block but also an AML suspicious transaction report These questions reflect a growing consensus that preventing and detecting APP scam payments is part of a bank’s AML/CTF duty, not just a “fraud prevention” courtesy. In short, scams and mule networks are now facilitating predicate offenses to money laundering, and regulators have signaled that financial institutions will be held accountable for detecting and reporting such activity as part of their AML obligations.

2025 Fraud Data Highlights: Credit Transfer Scams, Mules, and Cross-Border Flows

The latest fraud figures paint a vivid picture of the APP scam epidemic and its money laundering links. According to the joint EBA/ECB 2025 report, total payment fraud losses in the EEA jumped 17% year-on-year to reach €4.2 billion in 2024. The biggest contributor by far was fraud via credit transfers at €2.5 billion (up 24% YoY). This means credit transfer scams alone comprised roughly 60% of all payment fraud losses, underlining how heavily APP scams dominate the landscape. By contrast, card payment fraud accounted for about €1.3 billion (only ~31% of the total), and other instruments like e-money, direct debits, or ATMs made up the remainder.

Why do credit transfer scams yield such disproportionate losses despite relatively few incidents? A key reason is the high average loss per scam. Credit transfers tend to be higher-value transactions, so when they are subverted by scams, the amounts are substantial. The average fraudulent credit transfer transaction in 2024 was over €2,000. In many cases, victims are tricked into sending multiple thousands of euros (savings, loan proceeds, etc.) in a single scam. These large amounts per incident quickly add up, a “low” fraud incident rate can still translate into heavy losses when each case is expensive and often impossible to recover after the fact. Indeed, industry data shows that once money is sent to scammers, recovery rates are very low and getting worse, as funds are immediately dispersed through mule accounts or crypto exchanges. In 2024, net fraud losses (funds gone for good) grew even faster than the fraud transaction count, implying criminals are getting more effective at laundering the proceeds out of reach.

Another salient data point is the cross-border nature of these fraud flows. Most everyday payments are domestic, yet fraud incidents are disproportionately cross-border. The report highlights that a large share of credit transfer fraud (and card fraud) involves funds moving across country lines. For card fraud, around 30% of fraud value in 2024 flowed to recipients outside the EEA For APP scams via bank transfers, it’s common for money to be sent from a victim in one country to an account in another, often quickly forwarded through multiple countries. This cross-border element makes recovery and investigation far more difficult, and it mimics traditional money laundering patterns (using overseas accounts to evade detection).

Crucially, money mule accounts underpin this fraud ecosystem. Banks are observing that the accounts receiving APP scam funds are frequently part of organized mule networks. A typical scenario: a fraudster convinces victims across different banks to send money to various mule accounts; those mules then rapidly transfer the funds onward (sometimes splitting into smaller amounts or converting to crypto) to obscure the trail. The report and law enforcement updates indicate that thousands of such mule accounts are active in Europe, acting as the first funnel for scam proceeds. The involvement of these accounts means that each APP scam incident is not an isolated fraud, it is the front end of a laundering operation. The data reinforces that point: fraud affecting instant payments (SEPA Instant Credit Transfer) often entails smaller average amounts than regular transfers, but in high volume, suggesting fraud rings pushing many small payments through mule pipelines. For compliance teams, this means patterns like multiple incoming credits followed by quick outbound transfers should raise immediate suspicion of mule activity and trigger both fraud countermeasures and AML inquiries.

Regulatory Shifts: PSD3, AMLD6, and AMLA Raise the Bar

European regulators have responded to the APP scam wave with sweeping regulatory shifts that tie fraud prevention closer to AML responsibilities. The forthcoming Payment Services Directive 3 and accompanying Payment Services Regulation (PSD3/PSR) specifically include measures to combat APP fraud, effectively increasing PSPs’ liability and pushing real-time intervention capabilities. Meanwhile, the 6th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD6) and the creation of a new EU Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA) expand the AML regime to explicitly cover fraud-related flows and broaden oversight to fintech and payment institutions. Together, these changes signal that preventing and reporting scams is now a regulatory expectation on par with traditional AML/CTF duties.

PSD3/PSR, Fraud Liability and Real-Time Detection:

Under the political agreement reached in late 2025, the PSR will significantly strengthen consumer protections against fraud. Payment service providers (PSPs) that fail to implement appropriate fraud prevention mechanisms will be held liable for customers’ losses. Notably, the new rules target impersonation scams head-on: if a customer is tricked by someone pretending to be, say, a bank official and approves a fraudulent payment, the PSP must refund the full amount of the scam (provided the victim reports it to the police and the bank). In other words, for many APP fraud cases the default liability will shift from the customer to the PSP, a dramatic change from today’s norms. This creates a strong incentive for banks and fintechs to stop scams before funds leave the account.

To help achieve that, PSD3/PSR provisions push real-time fraud detection capabilities into daily operations. PSPs will be required to verify payee identity on credit transfers (the “Confirmation of Payee” system), if the account name doesn’t match the intended beneficiary, the PSP must warn the sender or even refuse the payment. This aims to prevent classic APP scams where victims are duped into sending money to an account under a fraudster’s name. PSPs will also explicitly have the right to block or delay a payment when their systems detect strong evidence of fraud in progress. This is a shift from earlier rules that left banks uncertain about intervening in customer-authorized payments, the new regulation empowers and expects providers to pause suspicious transactions to prevent losses. Furthermore, receiving institutions must freeze incoming funds that look suspicious (for example, if an inbound transfer appears connected to a known scam). The PSR package also mandates that PSPs implement spending limits and allow customers to block certain payment types, to reduce exposure to fraud. Collectively, these measures mean that European PSPs will face direct liability for APP scam losses and are being armed with both the obligation and authority to monitor and halt suspect payments in real time. The era of instant payments thus comes with an expectation of instant fraud screening, blurring into what we’d traditionally consider AML-style transaction monitoring.

AMLD6, Fraud as a Predicate Offense & Reporting Expectations:

In parallel, Europe’s new AML/CFT legislative package (effective 2024-2025) reinforces that fraud is officially a predicate offense for money laundering. The Sixth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (6AMLD) enumerates 22 categories of predicate crimes, and “fraud” is on that list. This means that funds derived from APP scams are legally proceeds of crime, and moving or hiding them constitutes money laundering. AMLD6 harmonizes this across all member states, leaving no doubt that institutions must apply AML controls (customer due diligence, monitoring, suspicious reporting) to scenarios involving fraud proceeds. In practical terms, if a bank knows or suspects that certain transactions involve scam proceeds, for instance, a series of credits from different individuals that match a known fraud pattern, it is obliged to report a Suspicious Activity (SAR) to its Financial Intelligence Unit, just as it would for suspected drug money or corruption funds. There is no de minimis threshold excusing small scam transactions from scrutiny; even if each victim sends a relatively modest amount, the aggregated scheme can trigger AML red flags (multiple small incoming transfers can be just as suspicious as one large transfer). Regulators are expecting banks to update their transaction monitoring scenarios to incorporate these patterns, ensuring that what might have been seen as “just fraud” is now caught in the AML net as well. Additionally, AMLD6 expands liability to those who facilitate money laundering (like mule recruiters or money mule account holders), meaning enforcement can reach deeper into these fraud-laundering networks. All of this raises the stakes: banks that miss obvious scam-related laundering activity could face AML compliance penalties, not only fraud write-offs.

AMLA, A New EU Authority Watching Fintechs and PSPs:

The creation of the Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA) marks another paradigm shift in oversight. Starting operations in 2025 and ramping up through 2026-27, AMLA will centrally coordinate and eventually directly supervise the EU’s riskiest financial institutions, including select banks, payment firms, and crypto providers that operate across multiple countries. This means large fintech PSPs and digital banks could fall under pan-European AML supervision for the first time. AMLA’s mandate explicitly covers emerging sectors like crypto-asset service providers (CASPs), in fact, its first public focus has been on expecting high AML standards in the crypto sector, but it will also be assessing payment institutions and fintechs, especially those with significant cross-border business. By 2026, AMLA will be issuing detailed guidance, conducting “convergence reviews,” and working with national regulators to ensure consistent enforcement of AML rules across the EU. Although direct supervision of a subset of institutions (perhaps ~40 major groups) will only start in 2028, the expectation-setting has begun. For PSPs, this means more scrutiny on whether their AML programs cover fraud-driven activities like APP scams and mule accounts. AMLA is likely to push for advanced practices, e.g. that firms use data analytics to spot scam patterns, share fraud risk data with peers (as enabled by PSD3’s data-sharing provisions), and treat consumer fraud incidents as potential AML events. The establishment of AMLA signals that AML compliance is no longer just a banking issue: fintech companies, payments processors, e-money and crypto firms are squarely in scope for tough supervision. The authority’s view, backed by new regulations, is that stopping fraud and stopping money laundering are part of the same mission to protect Europe’s financial system.

Operational Implications: Breaking Down Silos Between Fraud and AML

For payment providers, these developments necessitate a fundamental re-think of internal operations: fraud prevention and AML compliance can no longer run on separate tracks. Traditionally, a bank’s fraud team might focus on fast-moving threats (phishing scams, unauthorized transactions) using rule-based detection engines, while the AML team handled after-the-fact monitoring (like filing SARs on unusual client activity) using separate systems. That siloed approach is now viewed as a vulnerability. Modern fraud schemes like APP scams exploit any gaps between front-line fraud checks and back-end AML controls. In response, firms are moving to merge their fraud and AML workflows into a more unified “financial crime” operation.

Practically, this means AML programs must start ingesting fraud intelligence and vice versa. Confirmed fraud incidents and risk indicators should immediately feed into AML monitoring systems. For example, if a certain bank account or crypto wallet is identified as a mule receiving scam funds, that identifier should be added to AML watchlists and transaction monitoring rules without delay. Likewise, known fraud typologies, say, multiple new payees added followed by large outgoing transfers, or rapid sequences of incoming credits that empty out quickly, need to be built into AML scenario models. By incorporating these fraud patterns, AML teams can spot laundering in progress (the “follow-on” to the fraud) and raise timely alerts.

Conversely, fraud teams should escalate suspected scam transfers as AML events. If a fraud analyst intercepts a dubious payment (e.g. an elderly customer wiring an uncharacteristically large sum to a new overseas account under urgent instructions), that should not only trigger a fraud intervention (like calling the customer) but also an internal suspicious activity flag for further investigation. Even if the customer ultimately approved the transaction (perhaps convincing the bank it was legitimate at the time), the institution can subsequently file an SAR on that flow of funds, which alerts authorities to the likely mule account receiving the money. In essence, every APP scam attempt is a two-sided crime, the victim side and the recipient side, and while the victim’s bank might classify it as fraud, the recipient’s bank should treat the unexplained inbound funds as suspicious proceeds of crime. Bridging fraud and AML operations ensures that such hand-offs happen seamlessly: the moment one side detects a scam, both sides (sending and receiving) act in concert.

To enable this, many firms are implementing shared case management and alerting systems. Rather than separate case queues for fraud investigators and AML investigators, a unified platform allows teams to see the full picture of a case. For instance, if a customer reports an APP scam, the fraud team can reimburse or block further payments, and simultaneously an AML case can be opened to trace and report the funds that already left. In real time, the fraud operations center might block a transfer mid-flight and automatically log an AML compliance alert about that incident. This kind of joined-up workflow was rare in the past, but new regtech tools make it achievable (and new rules make it necessary). The result is a more holistic risk view: patterns that might not trigger an independent AML alert (if each transaction is below a threshold or doesn’t fit a classic profile) will be detected if the fraud context is considered. For example, a series of incoming payments to an account might look normal to AML systems in isolation, but if those senders are confirmed scam victims (data the fraud team knows), an integrated system can connect the dots and flag the account immediately.

From an organizational perspective, this convergence often involves cross-training staff and establishing joint investigative units. Many digital banks and fintechs are creating “financial crime” teams that handle both fraud and AML, or at least ensure daily communication between the two functions. Alerts are reviewed in tandem, and expertise is shared, a fraud analyst might recognize a new scam script, while an AML analyst might recognize a layering technique, and together they can piece together the full scheme. The tone from regulators is reinforcing this: European supervisors now expect institutions to “deal with scams under the banner of anti-financial crime measures”. In practice that means if you stop a fraudulent payment, you should still analyze it for AML implications; if you file an AML report, you should consider if it stems from an underlying fraud that needs prevention measures. The silos must come down. As one expert succinctly put it, fraud prevention can no longer be siloed from AML compliance, they are “two sides of the same coin”.

Guidance for PSPs: Integrating Fraud and AML Programs

Given the above, what steps can payment service providers take to integrate their fraud and AML efforts? Below are key practices emerging as industry best practices to address APP scams through a converged approach:

- Real-Time Behavioral Analytics: Deploy unified monitoring systems that analyze customer behavior and transaction patterns in real time. Establish baselines for normal behavior and flag anomalies the moment they occur. For example, if a typically low-activity customer suddenly initiates a high-value international transfer, a real-time system should catch this deviation and trigger an immediate review or hold on the payment. These systems, often powered by AI/ML, help detect the fast-evolving tactics of APP scammers (such as new phishing ploys or mule account behaviors) as they happen.

- Converged Fraud + AML Monitoring: Bridge the gap between fraud detection and AML transaction monitoring by using a shared platform or data lake for risk scoring. Instead of running separate rule engines, modern solutions allow financial institutions to evaluate transactions for fraud indicators and AML risks simultaneously. This yields a more complete risk picture: for instance, an outgoing payment might not trigger a standalone AML alert based on amount or profile, but if the receiving account has been flagged by the fraud team (e.g. reported in a scam by another bank), the combined system can catch it. Converged monitoring ensures there are fewer blind spots, the same real-time rules engine can stop a payment and log an AML suspicious activity case in parallel, closing the cracks through which criminals previously slipped.

- Shared Risk Scoring and Alerts: Implement a unified risk scoring model that incorporates inputs from both fraud and AML analytics. For example, feed fraud risk signals (phishing reports, malware flags, compromised account warnings) into customer risk profiles used by AML systems. If a customer falls victim to a scam, their profile risk should spike, alerting compliance to potential unusual transactions. Likewise, an account that triggers an AML alert for suspicious inflows could have its fraud risk level elevated across the institution. Ensure that alerts, whether initially flagged by fraud monitoring or AML rules, are accessible to both teams through a common dashboard or case management tool. A joint alert workflow means that when one team investigates, they can easily loop in the other if needed (for instance, fraud investigators can refer a case for SAR filing, or AML investigators can ask fraud units to block transactions immediately).

- Joint Investigation and Response Teams: Formalize collaboration through cross-functional teams or protocols. Some PSPs have set up “fusion centers” or weekly risk calls where fraud and AML units review emerging threats and coordinate responses. Even without a dedicated fusion center, firms should define clear hand-off procedures (e.g., how a fraud case that reveals a money mule gets escalated to AML, and how an AML finding about a suspicious beneficiary gets fed into fraud prevention to block future payments to that account). Consider creating a task force specifically for APP scams and mule networks, drawing staff from fraud, AML, cybersecurity, and customer support. This team can jointly develop scam response playbooks, for example, when a scam is confirmed, fraud ops will attempt recovery and customer reimbursement while AML will rapidly file reports and liaise with law enforcement. By treating APP scam incidents as organization-wide emergencies rather than siloed issues, PSPs can drastically improve their success in disruption and recovery.

- Data Sharing and Collaboration Beyond the Institution: Since APP frauds often span multiple institutions, collaborate with the wider ecosystem. Take advantage of emerging frameworks (like the PSD3 provisions for inter-bank fraud information sharing) to exchange intelligence on confirmed scams and mule accounts in a privacy-compliant way. Industry consortia and fraud hubs can allow a bank that suffered a scam to alert other banks about the accounts involved, so those receiving banks can freeze funds or monitor those accounts. This industry cooperation blurs into AML as well, since it essentially creates a collective defense where patterns spotted by one institution (or advised by law enforcement) can prompt suspicious transaction reporting across many institutions. PSPs should actively participate in such initiatives and ensure their internal systems can quickly incorporate shared external risk indicators (e.g., a blacklist of beneficiary IBANs linked to scams).

- Customer Education and Stronger KYC: On the prevention side, continue investing in customer education and phishing awareness, this is now also an AML issue, because informed customers are less likely to fall prey and fund criminals. Under PSD3, banks will have formal obligations to educate users about fraud risks. Reducing the human vulnerability through campaigns, in-app warnings (“Beware: scammers may call pretending to be bank staff”), and training customer service to spot scam signs will lower incident rates. Simultaneously, bolster your KYC and onboarding controls to screen out potential mules, many institutions are tightening checks on new accounts that show red flags (fake documents, inconsistent information) because these could be opened solely to launder scam proceeds. By preventing mule account openings or catching them quickly, PSPs remove the infrastructure that enables APP fraud at scale.

Adopting these practices requires investment in technology and a cultural shift inside institutions. The payoff, however, is significant: a truly integrated fraud/AML program can stop fraudulent payments in flight and generate the required intelligence to help authorities dismantle the criminal networks behind the scams. It also positions institutions to better comply with the incoming regulations that demand such convergence.

Unified Case Management & Real-Time Alerts: Flagright’s Perspective

Financial crime solution providers have taken note of this convergence trend and are building tools to facilitate it. A prime example is Flagright, a regulatory technology firm that has been championing unified fraud and AML case management. Flagright’s approach underscores that when fraud prevention and AML compliance share a single, real-time view of risk, firms can break down the traditional silos and respond to threats much faster. In thought leadership forums, Flagright experts have emphasized using modern, cloud-based platforms to achieve sub-second risk scoring across both fraud and AML domains. Such platforms enable a suspicious transaction to trigger an instant fraud block and simultaneously log an AML suspicion case, ensuring nothing falls through the cracks during those critical minutes in an APP scam scenario.

The concept of unified case management means all alerts and investigations, whether prompted by a fraud trigger or an AML trigger, reside in one system where both teams can collaborate. Flagright and similar providers offer centralized dashboards where, for example, a fraud analyst can see the AML risk profile of a customer alongside fraud indicators, or an AML investigator can see that a customer was recently the target of a phishing attempt. This “single source of truth” greatly improves efficiency and insight, as patterns become apparent when data is combined. In other words, integrated tools directly translate to better outcomes: fewer false negatives (missed incidents) and a stronger, faster response to those that do occur.

Another aspect Flagright highlights is real-time alerting, the ability for the system to not just batch-process overnight or trigger manual reviews, but to analyze transactions on the fly and send immediate alerts to both fraud and compliance teams. This capability is crucial in an era of instant payments. If a scam is detected only after funds have left and been withdrawn by a mule, it’s too late. A unified platform with real-time analytics can pop up an alert (or auto-decline the transaction) the moment something looks amiss, buying valuable time to stop fraud and meet the tighter regulatory expectations for vigilance.

By adopting such unified solutions, PSPs can operationalize many of the guidance points described above. Unified case management means the fraud and AML teams are literally on the same page, working through a shared queue of cases with full context. Real-time, unified alerting means the institution’s risk engine is always watching transactions for both fraud red flags (e.g. scam narratives, device anomalies) and AML flags (e.g. mule account patterns, sanction hits), and can act on the combination of those signals instantly. Flagright’s thought leadership in this space positions it (and similar regtech firms) as a valuable partner for fintechs, digital banks, and payment processors seeking to modernize their defenses. By bringing technology that embeds convergence by design, these providers enable even smaller or newer institutions to implement a sophisticated, joined-up fraud+AML program without having to build it all in-house.

In summary, the tools and platforms now exist to support the convergence of fraud and AML functions. The onus is on financial institutions to leverage them. Those that do, by working with innovative solution providers or developing in-house unified systems, will be better equipped to meet regulatory demands and protect their customers. Flagright’s perspective as a leader in this field is clear: unified defenses are not just possible, but essential in the fight against modern payment fraud.

Conclusion: No More Silos, 2026 and Beyond

The writing on the wall is unmistakable: APP scams will no longer be treated as an isolated “fraud department issue.” Going into 2026, European payment institutions must collapse the wall between fraud prevention and financial crime compliance. The 2025 EBA/ECB fraud report serves as both a wake-up call and a roadmap. It shows that even as overall fraud incident rates remain low, the fraud that does occur is high-impact, fast-moving, and often cross-border, exploiting any cracks in banks’ control frameworks. To counter this, firms need to embrace an integrated strategy where protecting customers from scams and preventing illicit finance are viewed as two sides of the same mission.

This convergence is not just a best practice but is being actively mandated by regulators. With instant payments becoming the norm, regulators are nudging (and in some cases shoving) the industry toward real-time, unified fraud and AML controls. Siloed approaches or after-the-fact review processes won’t suffice when transactions settle in seconds and social engineers can bypass front-line checkpoints. The financial institutions that succeed in this new landscape will be those that break down internal barriers and foster a culture of shared responsibility for combating financial crime. This means unifying people, processes, and technology, fraud analysts and compliance officers working hand-in-hand, backed by analytics that adapt as quickly as the fraudsters do.

The year 2026 is poised to be a turning point. As PSD3/PSR moves toward implementation and AMLA begins shaping supervisory expectations, the cost of inaction is rising. Firms that cling to fragmented defenses may find themselves facing not only higher fraud losses but also regulatory censure for AML lapses. By contrast, those that invest in unified, real-time defenses will not only mitigate scam losses but also build customer trust and resilience in an era of digital finance. The endgame is clear: protecting the integrity of payments demands an integrated approach. APP scams, mule networks, and other fraud typologies are now firmly part of the financial crime risk spectrum. To stay ahead of these threats, banks, fintechs, and PSPs must treat fraud and AML as a joint front, deploying the tools, team structures, and mindsets that allow them to anticipate and thwart scams as a matter of compliance as well as customer duty.

In sum, the siloed era is ending. The coming year will witness Europe’s financial institutions increasingly operate as unified financial crime-fighting units. By heeding the lessons of the latest fraud data and embracing the new regulatory paradigm, the industry can make 2026 the year it finally turns the tide on APP scams by attacking them on all fronts, as both fraud and money laundering threats, in one concerted effort.

.svg)

.webp)